On the importance of communal spaces

A muraled garage door in Berlin-Kreutzberg.

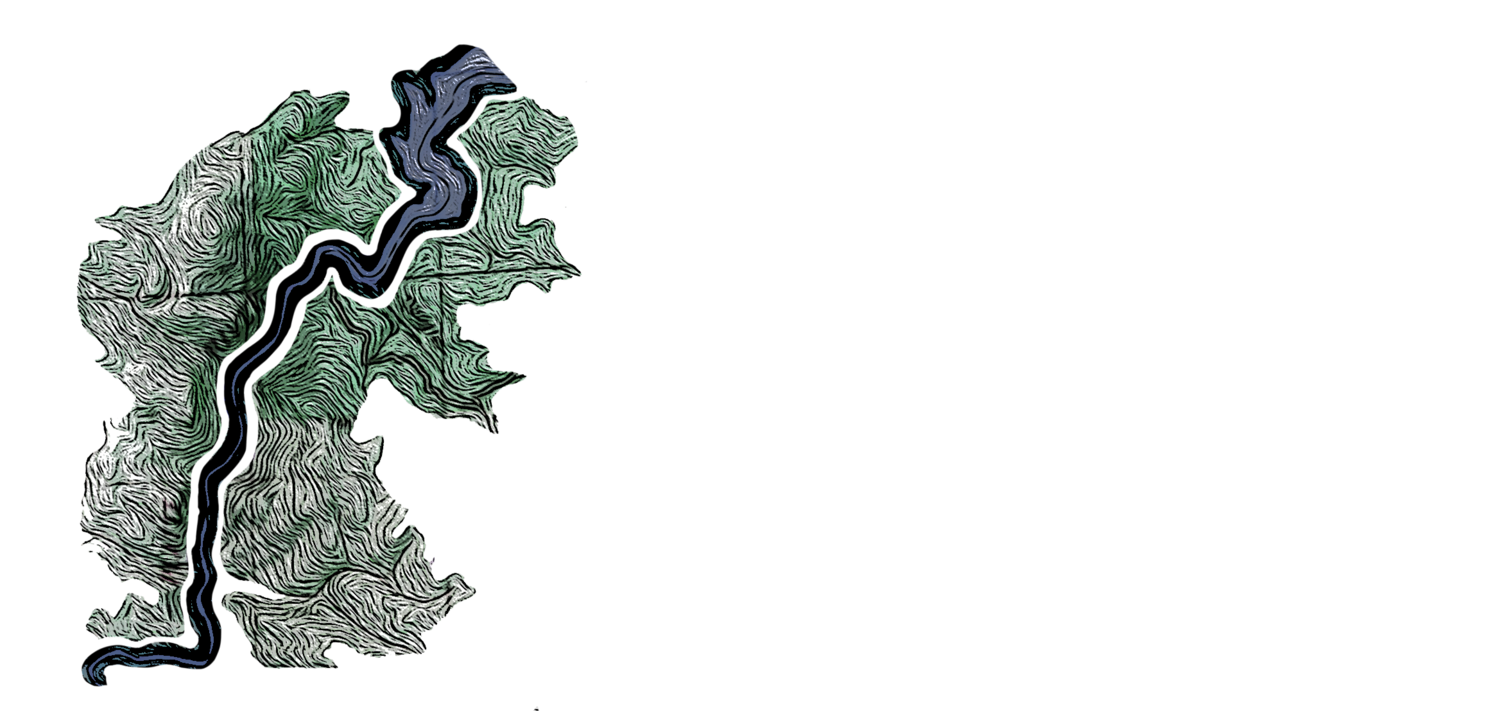

I spent an afternoon wandering Berlin’s Kreuzberg, thinking about spaces and borders. I won’t try to represent the history of the neighborhood, but based on my friend Jesse’s tour guiding, it sounds like the former border quartier along the Berlin Wall is fighting (successfully, currently) to maintain its international/immigrant/punk/squat/commune culture and protect its public spaces from developers, speculators, and corporate capitalism. The path of the Wall, a bombed-out train station, and the decommissioned Tempelhof airport grounds are all sites claimed and transformed by locals into public green space that hosts daily parties, public art (commissioned and guerilla), communal gardens, and informal residences of varying permanence.

Along with Germany’s social safety net, Berlin’s rent control laws, and the neighborhood’s mutual aid ethos, these communal spaces revolutionize how residents are able to live in this neighborhood – small, simple apartments, often shared; social kitchens available for use, and also often offering pay-what-you-can meals; shared tools and other resources; all supporting a far different relationship with income, ownership, community, and definitions of (self-)sufficiency.

In June I spent two weeks in Bulgaria, attending an annual conference by international contemporary performing network IETM. This included a 2-day tour of central Bulgarian venues, a celebration of a recently opened arts complex for the independent performance scene in Sofia, and a trip to the Black Sea city of Varna to help local artists advocate for the creation of a similar center there.

Venues across most of Europe are housed in government-owned buildings, with negligible rents and robust public funding, including support for programming and personnel, and mandates to present a curated mixture of local and touring works. The Bulgarian venues we visited were mostly founded through artist-led initiatives, with government support but staffed with producers and curators anchored in the arts scene, not the government bureaucracy. Crucially, European venues are rarely managed (and resourced) by performance companies, but rather operate as presenters, partners, and service providers for many local companies. That centralizes production costs (technical equipment and personnel, ticketing, marketing distribution, etc.), allowing artists to focus more on making art. The venues’ curatorial voices allow them to develop a standing audience, connecting artists with new viewers and also with artists creating similar work.

In Denver, most venues work in one of two ways. Either they’re owned by the city, managed by city staff (with varying relationships with the local arts scene), and operated on a more or less subsidized first come first served rental basis; or they’re owned (leased, mostly) and operated by performance companies that dominate the venue’s programming, rent out occasional weekends at rates that help them pay their retail-priced rent, and struggle constantly to keep their doors open.

The few local presenting venues (DU’s Newman Center, parts of various suburbs’ performing arts centers’ program) don’t present local work, instead focusing on works from outside Colorado. Uniquely, the Denver Center for the Performing Arts (DCPA) enjoys a lifetime lease of its spaces at the city-owned Denver Performing Arts Complex (DPAC, not to be conflated with its independent non-profit tenant). Despite a mandate attached to its massive Tier I funding stream from the seven-county Scientific and Cultural Facilities District (SCFD) for it to collaborate with local artists and Tier III organizations, DCPA rarely produces local work or hires local artists in lead roles.

That leaves local artists running productions themselves, operated by their own staff and volunteers, attended by their individually maintained networks of fans and followers. This is wasteful – it increases each production’s costs substantially, and reduces the works’ reach, decreasing both impact and ticket income. It heightens inequality, raising barriers to entry and prioritizing business savvy over quality and cogency of the work (I know I know, dangerous words – but can we please wade into the messy conversation of healthy criteria for adjudication and curation?). Most companies fold within five years, and Denver struggles to keep artists here and working in their forms.

A presenting venue focused on local independent work would revolutionize Denver’s performing arts culture. The substantial programmatic funding it would need would flow largely to artists. Projects would need less overall funding, because of the venue’s centralized production resources, again increasing funds available to pay artists. Organizations and lead artists could work on a project basis, instead of programming seasons designed to keep audiences engaged and operating budgets at a level needed to support year-round production support staff). This opens doors to more diverse working styles and personal economies, and lowers the bar to entry for strong project concepts by new voices. Clear curatorial practices would create a venue that audiences trust even when they don’t know the artist, introducing them to new voices and increasing each work’s impact and the venue’s available funds. And having a center like this would pull the performing arts community together, incentivizing connective behavior instead of the current norm of closed-off individual self-sufficiency.

So, yeah, communism. Or social democracy, anyway.

My Kreutzberger colleague recalled a recent visit from a Colorado friend with committed libertarian leanings and a deep love of animals. They visited Kreuzberg’s free, communally maintained petting zoo, and she struggled to wrap her head around the fact that there was no money being exchanged for her to pet the goats – “Wait, this is how communism works?!” Yes. In fact, the same thing is at work in Golden’s free public waterpark along Clear Creek. Resources held as common good, so that no one can extract profit from someone else to use it.

But you can look at it just as easily through capitalist lenses of cost efficiency (but within a community or industry instead a single business), economic magnifiers, and cost-savings on public services that are supported by volunteers and mutual aid initiatives alongside paid labor. You can even call it a trickle-down economics success story, if it helps you convince any Cold Warrior communo-skeptics in your orbit…

Rant over (for now). This is one of my oldest, most used soapboxes – sorry if it’s boring and familiar, or if I’m skipping over important points. Please reach out with questions, further conversation, and massive seed funding (and leadership ideas – Control Group shouldn’t be at the center of that initiative any more than any other single company or artistic voice) for a robust local presenting venue – maybe at approximately 8th and Navajo?

-PATRICK 8/12/24