Border Crossings

I spent the week after the IETM Plenary banging around Bulgaria with my friend Jesse. We tried relaxing on a couple Black Sea beaches, but our dour Central Europeanesque outlooks and Protestant-turned-struggling-artist work ethic got the better of us, and we found ourselves driving to the furthest southeast corner of EU-Europe, to stare across the Resovo River toward Turkey. Jesse had crossed the border northwards on a bus in the middle of the night four years earlier, after getting stranded in Turkey for several months at the beginning of Covid. Stuck in a tiny Antalya apartment for months, unwelcome in the streets as a White foreigner, this journey out of purgatory barely registered the actual moment of passing from foreign to – well, less foreign soil, based on Schengen agreements around free passage in Europe. And so we sat there, staring at the 50-foot flags flying on either side of the estuary, and at Turkey’s military installations, and placards on the shoreline forbidding swimming.

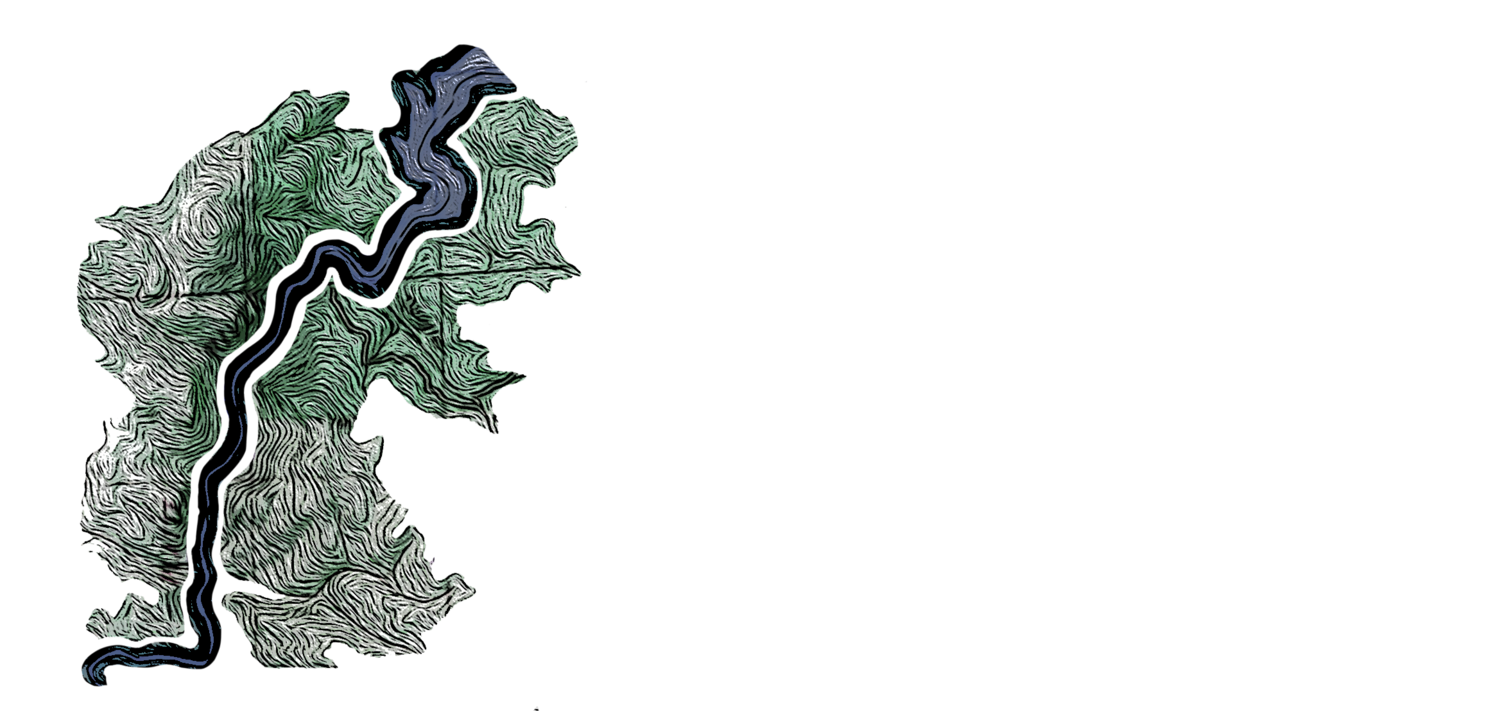

A few days later and 300km east, we visited the ruins of The Ancient Sanctuary City of Perperikon. Occupied starting in 5,000 BCE, it was ruled from Antiquity through the Middle Ages by successive waves of conquerors – Thracians, Romans, Goths, Byzantines, Bulgarians, and Turks, as power and borders washed back and forth across the Balkan peninsula. Perhaps some of these border crossings were simple affairs: messengers delivering news that a new ruler had claimed the region. Probably, considering the site’s defensibility and military tactical value, it more often was less simple and more violent.

The next day I drove Jesse as deep into the Rhodope Mountains as there was road for, and dropped him off in the village of Mochure, where he set off on foot over a mountain pass and across the border into Greece.

He didn’t make it. He was flagged down by border police halfway up the pass (he made it further because his olive shirt and military issue pack convinced them he was Bulgarian military). But the interaction stayed benign, even jovial, and they drove him down to the nearest bus stop, where he caught a two-day series of buses to a much less pleasant hike along a highway out of Bulgaria and into a paradise of other stories.

Meanwhile, I continued east through the Rhodopes to the Devil’s Throat – a massive natural cavern with a river flowing/falling through it. This awe-invoking, mystical subterranea was the path Orpheus took to return from the Underworld, after paying for his passage and that of his wife Eurydice with a song so beautiful it moved Persephone to convince her husband Hades to release them. And so they climbed up the Devil’s Throat toward the light streaming through verdant mist. But just shy of the cave mouth, a bare step from the sunlight of the world above, Orpheus risked a glance backwards to make sure Eurydice was still following him. This innocuous, maybe inadvertent moment of transgression broke his agreement with Hades, and he watched as Eurydice was pulled back down the Devil’s Throat, never to return to the world of the living.

In the narrow interstitial space of a border, one wrong move can have dire consequences. People with different documents and status can be torn in opposite directions, passing easily or disappearing forever.

But in Devil’s Throat as at the Poland-Ukraine border, I came through unscathed, seemingly unnoticed by the Gods that rule the Interstitia.

And now I’m here.

Lviv is uncomfortably normal. It’s a beautiful city, familiar in many ways from past travel to Sofia, Prague, less groomed parts of Vienna. It’s fascinating to see the layers of history, as borders washed back and forth over the city over the last millennia – Vikings, Mongols, Tatars, Poles, Lithuanians, Hapsburgs, more Poles, Soviets. Another situation of “We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us.” At various periods Lviv was one of the most international cities in Europe, and known for its religious and cultural tolerance. For a long time (but not at crucial, deeply horrific moments) it was renowned for its embrace and integration of Jewish culture.

There are telltale signs here of Ukraine’s turbulent recent history and present – the pothole-riddled highway into town; a general quietude even in busy plazas; boarded up, sandbagged windows; closed businesses and cultural sites. It’s a place with very little crime, but an ease around transgressing – climbing around on the disregarded ruins of a hilltop citadel, watching sunset from the top of a half-built high-rise. But it’s only in moments that the background awareness of war on the horizon pushes to the forefront: setting up the air raid warning app on my phone; looking out at the total darkness in the streets after curfew (midnight this far west, earlier closer to the front); realizing how many young men I’ve seen with prosthetic limbs… Then realizing how few men under 60 I’ve even seen…

I was told to carry my passport at all times, to avoid forced, immediate enlistment in the army – a common enough occurrence that it will dictate our travel plans to Zakarpattia this weekend. I imagine young Ukrainian men living in a constant border-crossing mentality, never sure when the world and their agency in it could change suddenly, with grim, irreversible consequences.

So I’ll go and contribute a small piece of my privilege by teaching movement, performance, selfcare, and intercultural connecting to a group of Ukrainian youth for whom 25 (the age where military service can no longer be put off) hopefully still feels a lifetime away.

-PATRICK 8/15/24